Introduction Preface Section 0: Cybernetic Eyes Section 1: The Quick Guide to the VSM Section 2: Case Studies Hebden Water Milling 1985 Triangle Wholefoods 1986 One Mondragon Co-operative 1991 Section 3: Preliminary Diagnosis Janus interlude Section 4: Designing Autonomy Section 5: The Internal Balance Section 6: Information Systems Section 7: Balance with the Environment Section 8: Policy Systems Section 9: The Whole System Section 10: Application to Federations Bibliography Links Appendix 1: Levels of Recursion Appendix 2: Variety  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |

Case Study 2: TRIANGLE WHOLEFOODS

Note: The material in this section was written in 1986, with additional material added in 1991.BackgroundTRIANGLE WHOLEFOODS, trading as Suma, began in the mid seventies with a loan of £4,000 and was supported by the five wholefood retail co-operatives in the north of England who agreed to buy everything they could through Suma. This gave Suma a guaranteed minimum turnover. Over the following three years, the number of wholefood co-operative shops in the region grew enormously to around 60 by 1980, and Suma prospered accordingly. Currently (1998) Suma operates in a 60,000 sq. ft. warehouse in Halifax, offers a range of about 7,000 products (3,000 in 1991, 5,000 in 1995), and distributes nationally with a growing number of exports. There is some in-house pre-packing and bottling. Recent years have seen the introduction of several own-label products and the growth of environmentally sound products. Suma has always attempted to base its working practices upon the needs of its members - job rotation and flexible working conditions are common. Equal numbers of men and women has generally been achieved. At the time I was applying these ideas, SUMA, consisted of about 35 workers with a turnover in the region of 6 million ECU. Some departments had evolved (transport, manufacturing, warehouse), there were two committees which considered financial and personnel matters, and the entire membership was supposed to meet for the weekly Management Meeting every Wednesday afternoon. This meeting was the only recognised decision making body within Suma, and as such had to deal with all departmental issues as well as Suma policy. It also had to ratify the recommendations from the committees. The problem which had triggered the VSM study was an almost universal recognition that the Wednesday meetings were not working. As the size increased, agendas were getting longer and longer, less and less was getting dealt with, arguments were common, and many people didn't like to have departmental matters voted on by a large group, most of whom had no direct experience of the issues. Consequently, members began to avoid the meetings, some decisions were taken unconstitutionally outside the meetings ("but someone had to decide and the Wednesday meetings are useless") and it was realised something had to be done. DIAGNOSIS:

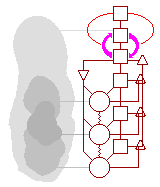

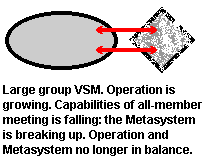

Suma had started as a small co-operative in which the Operation and Metasystem were balanced, as described in the study on HWMC. This is illustrated by the diagram shown on the right. As the numbers grew and the limits to this kind of viability were passed, problems began to emerge. The structure was still basically the same: the Operation was conceived as a single entity and the once a week all-member meeting was seen as the only Metasystem.

The complexity of the Operation was growing explosively in terms of new customers, new products, more services, and more manufacturing, and consequently viability required that the Metasystemic functions had to grow to cope. Some attempts were made to do this (the Finance and Personnel committees) but as the dominant Metasystemic body was the all-member meeting - and as numbers grew beyond 20 this became practically unworkable - the capabilities of the Metasystem were actually decreasing. In order to deal with this, departments had been set up to deal with the Warehouse, Transport, Manufacturing, Order-picking and so on, but they were still obliged to make all important decisions through the all-member meeting. Thus, they did not have the autonomy they needed to deal with their own problems. DIAGNOSIS OF SUMA 1986 (Structure only)The diagram opposite shows a VSM with five Operational units (O1 to O5). The environment is not shown as the current discussion is limited to the internal structure. METASYSTEM

System 5 (Policy) All member meeting. Doesn't work due to number of members. System 4 (Future planning) Almost completely absent. Performed by ad hoc groups. No 5 year plans. No marketing direction. No formal market research. System 3 (Synergy) Some attempts by finance and personnel committees. Hampered by dynamics of all-member meeting. Needs continuous implementation. Some personnel optimisation through the weekly Rota. System 2 (Stability) Co-operative ethos and wages policy makes conflict of interests unlikely. Cash flow controlled. Weekly Rota. Fairly robust. System 1 (OPERATION) The 5 Operational units illustrated are the Warehouse, Transport, Order Picking, Manufacturing, and Order Taking. In all cases the problem is the same: the ability to organise the departments effectively is frustrated by the lack of autonomy. The departments, charged with their own internal organisation do not have the freedom they need to work effectively. CONCLUSIONS:

THE DOUGHNUT PROPOSALSFrom the above considerations, it became clear that Suma had to rethink itself into autonomous departments. It was equally clear that these departments needed to cohere into a single harmonious organisation. In April 87, four of us produced the Doughnut Proposals which involved local decision making, new functions to articulate the all-Suma Metasystem, and the replacement of the Wednesday meeting with a system of small meetings ("Sectors") which sent delegates to the articulation of System 5 which eventually became known as the "Hub". The Doughnut proposals involved two VSM fundamentals:

IMPLEMENTATIONThe First 9 MonthsAfter weeks of debate and lobbying Suma accepted the Doughnut proposals by 25 votes out of the then 29 full members. However, rather than a smooth transition to the structures we proposed, Suma accepted that Things Had To Change and proceeded to try a succession of ideas, some based on the Doughnut proposals, some on the original structures and others on a combination of the two. It was all very unsettling. One of the problems was that Suma had decided not to drop the old system and go for autonomous departments, but to run the two systems in tandem for a transitional period. While this seemed quite sensible, the old committees refused to relinquish any of their powers and it became clear that they were actually preventing the new structures from becoming effective. It also meant that meetings began to proliferate, as several groups thought it was their job to discuss a particular issue. After about 6 months of this, the four of us who had produced the original proposals re-convened and produced a further 7 proposals aimed at resolving the situation. Most of these were accepted and implemented immediately; the result still forms the basis of Suma's organisational structure. PROPOSALS AND OUTCOMESThe original proposals were seen as something of a leap in the dark, and most members only accepted them as it was clear something had to be done, and that hierarchical solutions were not acceptable politically. In the following pages I will take the original proposals (as they were written in 1987), recount what happened in the first few months, and how they developed into our current (1991) structure. It should be remembered that Suma has been subjected to many other influences over the last five years, and that the Doughnut proposals cannot take the credit for all that has transpired. The proposals describe the Operational elements as "Segments", the name was later changed to "Sectors". Similarly the "inter-segment committee" became known as the "Hub". PROPOSAL 1: FORMATION OF SEGMENTS"We propose that Suma formally divides into small groups of around 7 to 10 people. Each group would work as a close-knit team with responsibility for a particular area of Suma's Operation. Each group would be given as much autonomy as possible within Suma to deal with its own problems and pursue its own internal development." The Outcome: Initially very little changed. The theory was that departments could ask for more autonomy as they needed it. During the first year departmental budgets were set up, and thereafter departments had financial autonomy within these limits. And gradually they became more autonomous. We had originally thought that some small departments might group together into new Operational units - the Segments - but this didn't happen. The original departments stuck to their original form. Currently most departmental decisions are made internally: all departmental expenditure, and most personnel matters, are dealt with autonomously. It is now recognised that most jobs are fairly specialised and that it would be foolish to have everyone involved in everyone else's business. Most of the basic conditions for autonomous departments have now become established. Recent examples are

PROPOSAL 2: LIMITS TO AUTONOMY

PROPOSAL 3: CO-ORDINATION OF SEGMENTS"Some new functions will be needed to ensure the segments work in a positive way. We propose a new committee which is formed specifically to ensure the segments work together co-operatively. This Inter-Segment Committee would consist of one delegate from each segment and would meet once a week to deal with problems between the segments and to suggest ways of improving over-all performance. We see this committee eventually replacing both the F.C. and the P.C. and forming the basis on which the segments work together." The proposed new meeting, which became known as the Hub, began to meet just as we had intended. However, we had expected it to deal mainly with inter-departmental (nuts and bolts) issues whereas the vast majority of Hub agenda was taken up with all-Suma policy. Initially some internal departmental issues were taken to the Hub, but as the departments were supposed to be autonomous, the Hub referred them back. Essentially the Hub took over from the all-member meeting except for internal departmental issues. Currently, the system works as follows: Once a week everyone who is interested meets in Sectors: groups of about 10 people. They discuss all the issues in the Sector Pack which begins with the minutes from the previous week's meetings, any minutes from other meetings which are relevant, proposals from members and anything else which requires the scrutiny of the whole co-op. Sector minutes are kept carefully and each meeting sends one delegate to the Hub. The various delegates read the relevant minutes and then make a decision based on the majority view within the co-op. Usually this is straightforward, but some issues are very complex and each Sector may come to a different conclusion. The Hub will usually summarise these views, clarify the lack of consensus and send the issue back for further discussion. Sometimes it becomes clear that a subject requires further thought and as such is referred to a committee. Eventually most Sectors come to similar conclusions and the Hub formalises the decision. Most decisions are made quickly, a few require two or three trips around the Hub/Sector system, and very occasionally it becomes necessary to call a General Meeting of all members to resolve a particularly difficult issue. There are two further safeguards on this system:

These safeguards were introduced to ensure that the Hub did not develop into a managerial elite. In practice they are almost never used: but everyone knows they are there. PROPOSAL 4: ACCOUNTABILITY & COMMUNICATION"Some way must be found to measure what's going on in each segment so that information is available to co-ordinate and make decisions, and so that segmental Autonomy can be given clear limits. We propose the use of the system of indices, together with the Cyberfilter program to extract important information. This system puts the responsibility for segmental development on the segments themselves. The information from the system is an immediate representation of what's going on." [Note: The "Cyberfilter" referred to here was a specific implementation of a change-detection system, using the Harrison-Stevens Bayesian forecasting algorithm. This was just one of many potential approaches to detecting incipient instabilities, but one which found favour in mid 1970s VSM applications.] This proposal was without doubt the most radical: we were proposing to move to real-time regulation and to use cybernetic filtration of information in order to generate algedonics. (All of this is described in more detail in Section 6). There are several aspects to this system:

We ran some tests on the systems using the manufacturing department. The indicators measured daily were productivity, machine usage, wastage and happiness. Between them these indicators gave a complete picture of the goings on within this department. Although the calculation of indicators only took up a few minutes at the end of each day, the system was never formally adopted by the co-op. They were seen to be too difficult to use and at the time there was no interest in making departments accountable. Over the last five years I have used indicators in the pre-packing department to measure productivity, wastage and out-of-stocks, and still find the system as useful as it seemed originally. However, they are only used within the department - there is still no overall system to ensure the departments are accountable. The only formal system involves the buyers: every week the sales loss through out-of-stocks is measured and plotted as a time series. This is then put in the Sector packs so that everyone knows what is happening. If this indicator began to rise alarmingly, the whole co-operative would know. There are several other informal performance indicators including daily tonnage, daily sales, the number of lines of orders taken by the sales office, and so on. However the integration of these into formal reporting systems, specific limits to autonomy and overall accountability has never been undertaken. PROPOSAL 5: FUTURE PLANNING"Decision making has already been transformed in the organisational structure proposed so far:

"This leaves the issue of decisions concerning the outside world as it affects Suma, and long term strategic decisions." "We propose a new function within Suma to deal with these issues which:

For months, nothing happened whatsoever. Most of Suma's energies were taken up in dealing with the internal problems and the need for a Futures function was seen as a very low priority. The issues raised its head again in 1988 after the Hub/Sector system had become established, and this time was pushed hard by the Marketing Department who had recognised the need for a long term marketing strategy, and needed a Business Plan within which to work. Three members were elected and given the job of researching possible future strategies. A vast number of options were looked at, but nothing actually happened. No proposals were produced. Currently we have hired consultants to provide us with a 5 year business plan and they have recommended we set up a "Business Plan" group to administer the plan. However, it would appear that the mechanisms that are being proposed involve analysis of variance and will further strengthen the System 3 (internal control) function. They will not in fact address the need for a System 4 as suggested in these proposals. PROPOSAL 6: QUARTERLY GENERAL MEETINGS"As the general meeting would only be needed to discuss major policy decisions, they would only have to happen every three months. In exceptional circumstances they may be needed more regularly, and extra-ordinary GMs could be called by the Intra-Segment Committee at any time." As the Hub/Sector system became established it dealt with Policy matters so successfully that General Meetings (of the entire workforce) became almost unnecessary. Very rarely an issue proves to be too complicated to discuss in separate meetings, and it becomes essential to assemble all the arguments with all the members. This has only happened twice in the last few years. The new system also allows any 5 members to call an Emergency General Meeting for any reason whatsoever. This has been threatened a few times, but so far it has resulted in the re-discussion of the subject through the Sectors. Generally it is now accepted that General Meetings are unnecessary except in exceptional circumstances. REVIEW OF ORIGINAL DOUGHNUT PROPOSALSIt's clear that the concept of autonomous departments and the need for a Metasystem to cohere them has worked for Suma. It's also clear that some of the original details just didn't happen (for example the combination of departments into Segments) and that some of our ideas were re-worked by the co-operative. (For example, the Hub/Sector system was adopted to work almost exclusively with Policy and not with the practicalities of departmental optimisation). Five years later, it still seems that the basic ideas are sound although the way that we originally interpreted them was far from perfect. The aspect which we had completely misjudged was the actual implementation. After the acceptance of the proposals, I expected a fairly smooth transition with the support of most of the co-operative. The reality was that Suma generated a series of excuses for putting off the actual implementation (it's summer so lots of people are on holiday. Now we're getting ready for the Christmas rush ... ) and the actual process had to be pushed very actively. The details of the period of implementation are not of direct relevance to this case study, although it should be noted that embarking on a programme of radical change in any organisation can be an extremely hazardous occupation. FURTHER DEVELOPMENTSDuring the initial implementation, there was a particularly chaotic period during which the Hub self destructed and divested its powers into the Personnel and Finance committees. As these bodies were a) designed to deal with a non autonomous Suma, and b) able to deal only with specific issues and thus not capable of taking the overall, synoptic view, the situation was unworkable. In this context, three of the four original Doughnut members met and made a further set of 7 proposals: "If Suma decides to make another attempt at the Doughnut, it's essential to make a much more concerted effort to establish the new system: the old working methods have proved to be more deeply entrenched than we imagined." "Our proposals are as follows:

The crucial elements of the November 87 proposals were accepted and implemented, and still form the basis on which we organise ourselves. SUMMARY and ASSESSMENTIt is clear that the major parts of the System are now in place.System 1: Operation. The departments are autonomous within limits set by financial and personnel budgets. System 2: Stability. Co-operative working practices continue to keep inter-departmental problems to a minimum. There is now better cash flow control and a recent system of stock control. Stability is further helped by improved co-operative information systems (e.g. the weekly business info). System 3: Optimisation. The Finance and Personnel officers & their committees deal with allocation of resources, and a weekly Rota looks at the best ways of placing personnel. Occasionally committees are set up to deal specifically with optimisation: recently three members were given the task of looking at our job requirements and fitting the best people to each job. System 4: Future Planning. The Futures Committee exists although it is presently not functioning in the pro-active way which the VSM sees as fundamental. The eventual outcome is not clear at this point. System 5: Policy Suma continues to involve all members in all policy matters on a continuous basis and this has to remain one of the rocks on which the co-operative is organised. The link between System 1 and System 5 is crucial. The Doughnut proposals began a process of re-organisation which is still in progress. It would be misleading to say that all the proposals were accepted and implemented: it is more accurate to say that we pushed Suma in a particular direction and that the final outcome is the result of the way Suma adapted to that push. I view the application generally as a success. In 1986, the weekly General Meeting had become the most commonly perceived problem. In a recent survey the Hub/Sector system was not even mentioned in the members' list of dissatisfactions. Financially Suma has performed well during the last few years, and seems to be riding out the present recession. The enormous increase in Operational variety over the last three years make it reasonably certain that the pre-VSM structures would not have been able to cope. Had the Autonomy Proposals not been accepted, the only other alternative would have been democratically appointed managers, the introduction of authority-obedience procedures, and consequently the loss of perhaps the most important element of the co-op's success - the self management of most of its members. It also seems reasonably certain that without VSM theory, the proposals from the Autonomy Group would have been unable to answer many of the criticisms which were levelled at it. The VSM enabled us to present a complete and thorough package, and thus played a crucial role in the development of the co-op. Further Enhancements (April 1991)There are several areas in which the structure of Suma could still be improved.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||