Introduction Preface Section 0: Cybernetic Eyes Section 1: The Quick Guide to the VSM Section 2: Case Studies Hebden Water Milling 1985 Triangle Wholefoods 1986 One Mondragon Co-operative 1991 Section 3: Preliminary Diagnosis Janus interlude Section 4: Designing Autonomy Section 5: The Internal Balance Section 6: Information Systems Section 7: Balance with the Environment Section 8: Policy Systems Section 9: The Whole System Section 10: Application to Federations Bibliography Links Appendix 1: Levels of Recursion Appendix 2: Variety  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |

Section 3: PRELIMINARY DIAGNOSISIDENTIFICATION OF THE 5 SYSTEMS

Preliminary Diagnosis - How it WorksI was told this story by a colleague (referred to as GB) who lectures in Management Studies, and who uses the VSM as a tool in his consultancies. It gives such a clear picture of the use of Preliminary Diagnosis that I decided to include it at this point. He was telephoned one morning in connection with the proposed amalgamation of several businesses into an alliance designed to enable the member companies to combine their strengths, and thus compete more effectively in exporting their products. The group had done some preparatory work, but needed advice quickly. A meeting was scheduled for 2.00 pm that afternoon. Usually, a consultant needs several days to assess the situation and gather the background which is essential for sound advice. This was clearly impossible. So, GB arrived for the first meeting with a large piece of paper on which was drawn the outline of the VSM, that is the Operational units and Systems 2, 3, 4 and 5. As the meeting proceeded, he began to ask questions about the proposed organisation and to fill in the boxes in his VSM diagram. Operational units: the member companies. And so on. After the proposed organisation had been described, some of the boxes were empty and GB began to probe "How do you intend to ensure that the member companies work together in a more effective manner - won't you need someone to examine the various possibilities and to look for synergy?" Basically, he was looking for something to write in the System 3 box. This is the essence of the Preliminary Diagnosis. You define a function, look for the bits of your own enterprise which does it, and write it in on the relevant part of the diagram. The VSM is so thorough in its model of how a business works, that GB's clients were overwhelmed with "his" insight and made aware there were several aspects of the organisation they had completely overlooked. And all of this without any preparation. In your case, assuming you are looking at an existing business, the insights are unlikely to be so staggering. Problems with viability will have arisen and been dealt with, and somewhere the functions needed for viability will have been implemented. The question is - are they adequate? But whatever the context, you will be mapping your own organisation onto a VSM diagram, and this process is bound to affect the way you look at your enterprise. Step 1: DEFINE THE SYSTEM TO BE DIAGNOSED

During the diagnosis which follows, there are times when it's easy to lose track of exactly what is being studied. So its essential to begin the Preliminary Diagnosis with a clear statement of the organisation (or the parts of the organisation) you are looking at. Throughout this guide, this will be referred to as the System-in-Focus.

Before starting the Diagnosis and the identification of the systems needed for viability, you should list all the parts of the System-in-Focus as you see them. The list should be exhaustive as it will be referred to throughout the Preliminary Diagnosis. It will contain the Operational parts, the accounting functions, the management functions and so on. In compiling the list, keep one eye on your sketch of the various recursions and ensure that the items on the list refer only to the system-in-focus. It's likely that your first list will need revision and that one or two items will belong to another recursion. Check it carefully. As the Preliminary Diagnosis proceeds, you will be able to take the items on your list and allocate them to one or other of the 5 systems within the Viable Systems Model. Thus, the list will gradually disappear. If your organisation is perfectly Viable, the list will disappear completely and there will be 5 well defined systems giving the basis for viability. If not, either

Step 2: DRAW THE VIABLE SYSTEM MODEL IN OUTLINE

The diagnosis of your organisation will proceed by drawing a large diagram which will represent your System-in-Focus as a whole system. At this stage, the outlines of the three main parts of the VSM - Operation, Metasystem and Environment - will be sketched in. Between them they represent the overview of your System-in-Focus in its totality.

DRAWING THE VSM - from Step 2 - drawing the outlines

Notes:

Step 3: SYSTEM ONE - THE OPERATIONPURPOSE: To specify those parts of the system-in-focus which undertake System One (primary) activities. The first system in the Viable Systems Model is the entire Operation which will be composed of several Operational units. The Operational units undertake the System-in-Focus's basic activities. They will all be (smaller) Viable Systems in themselves, and thus must be able to maintain a separate existence. System One generates wealth and in a business, each element can be considered as a profit centre. If you are a manufacturing business, System One is the production units, the teams of people and machines which actually do the manufacturing. If you are a programming co-op, System One is the programmers or teams of programmers, perhaps divided into various specialist areas. If you are looking at a more complex organisation, you may have a System One which includes manufacturing, distribution, and warehousing. System One sounds straightforward, but is actually one of the most difficult areas to define clearly. For example, in the examples given above the computer department was a System One in the programming firm, but the computer department in the manufacturing company would have a support role and would therefore not be part of System One. Some people who are in basically service areas such as engineering maintenance may consider themselves important enough to be System One. The question is: are they part of what the organisation is really about, or are they back-up, facilitators, or support? If the answer is the latter, then they do not qualify as System One. You are now in a position to go back to the original list of jobs carried out by your System-in-Focus, and to list those which between them make up System One. Note: Each Operational unit is a VSM at the next recursion down and thus will include both the physical aspects and the management of one aspect of the Operation. So, for example, the trucks and drivers and the management of the transport department are found within that Operational Unit.) DRAWING THE VSM - from Step 3 - adding the Operational Units

This diagram shows the VSM with three Operational units high-lighted. There is no reason why you should have three, although it is unlikely that you have more than eight. The diagram also shows the parts of the environment which are specific to the Operational units.

Steps 1, 2 and 3: Example

So far you have drawn the VSM in outline and added

At this stage the Suma VSM looked as follows: SYSTEM IN FOCUS: Suma Natural Food Wholesalers MISSION: Warehousing and Distributing Natural & Ecological products.

Step 4: IDENTIFICATION OF SYSTEM TWO - examplesYou have now drawn in System Two on the VSM diagram. Examples of System Two are as follows: System Two: SumaSystem Two is generally performed by the co-operative ethos which prevents major conflicts between members. The weekly Rota allocates members to various jobs according to departmental needs, and thus stabilises the problem of too many people in one area and not enough in another. There must be good cash flow control, thus stabilising the tendency for huge surpluses and overdrafts. The recent stock-control system stabilises stock holdings and avoids an oscillation between vast stocks and goods going out-of-stock. System Two: MondragonMondragon provides a System Two by sharing profits and by mutual financial support. This resolves any conflict of one business benefiting at the expense of another. System Two: SchoolThe timetable is regularly cited as the ideal System Two. It takes care of double-booking, and resolves the conflict of several teachers all wanting the same rooms, projectors etc., etc. System Two: Manufacturing Company.System Two is the production schedule which performs the same stabilising function as the school timetable. It resolves the conflict which could emerge in competition for limited resources. Step 5: SYSTEM THREE - OPTIMISATIONPURPOSE: To identify those parts of the System-in-Focus which optimise the interaction of the Operational units, and to update the VSM diagram accordingly. A System Three StoryConsider a Viable System consisting of several dozen people trying to put out a fire by running to a nearby lake, filling a bucket and running back to throw the water on the fire. Each person with a bucket is an Operational unit. Each will be absorbed with his own job. The Metasystem - which may be one person sitting on the top of a ladder - will look at the whole system and may say "Keep to the left on the way down" (System 2 - stopping continuous collisions) or it may think about optimisation. Eventually she may realise that if everyone forms a chain and moves the buckets from hand to hand, then you only have to move the water and buckets, and not your own body weight. The same job can be done, but only a fraction of the energy needs to be expended. The extra efficiency which is generated as a consequence of acting as a whole system rather than an un-coordinated collection of parts is called synergy, and the generation of synergy is the essence of System Three. The Job of System ThreeIn all cases, System Three has the same function:

Synergy is of course the essence of co-operation: four people working together co-operatively may be twice as efficient as four people doing the same work on their own. The current task is to describe the ways that System Three functions within a viable system.

System Three - the Diagrams.

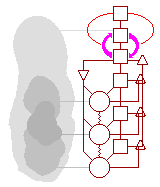

System Three is best thought of in the middle of a whole lot of activity. All around it the Operational elements are concerned with meeting the demands of their own environments (answering the phone, getting the orders completed on time, scheduling the trucks ...) and interacting with each other. System Three sits right in the middle of all this activity, thinking about ways of optimising the whole thing. Although this depicts nicely the relationship between Systems Three and One, it's a bit messy, and leave no room to illustrate the interactions between System Three and the rest of the Metasystem. So it's usually drawn above a stack of Operation elements like this:

This diagram shows the VSM with System 2, reduced to fit into the Metasystem's diamond and outlined, and a large System 3 added for emphasis. It's shown interacting with three Operational elements, although not as clearly as in the first diagram. This arrangement has much more in common with the human System Three - the base brain - which sits on top of the spinal column and optimises the working of the muscles and organs. We can now begin to describe the ways in which System Three over-sees the collection of Operational elements, looking for synergy. The Resource BargainSystem Three usually controls the purse strings. Resources are ultimately limited, and so it's essential for System Three to allocate them according to the global needs of the System-in-Focus. This requires System Three to look at the whole of System One, and to allocate resources so as to optimise performance. Thus System Three may say: "Your job is to get the goods to the customers in the most effective way, and we will give you £200,000 a month to do it. And as long as you do the job properly, you will continue to get the money." Obviously this will require lots of negotiations between all the Operational units and System Three, and it leaves System Three with enormous amounts of flexibility to generate synergy "Hmmmm .... if I put a few more resources into production they say they can be 17% more efficient. But that will mean cutting back on procurement and cut our margins by 1.52%. On balance that looks fine ...a much better allocation of resources." In a team, the resource bargain is more likely to involve allocation of people. "You do this and I'll do that, and things will work better ..." In a jazz band it could be allocation of time "The sax solo went on longer than expected, I'll cut down my break on keyboards." But whatever the particular example, manipulation of the resource bargain provides a means of optimisation. Operational AccountabilityOnce an Operational unit has been allocated its share of resources, it must demonstrate that it's using them properly. Thus the Operational elements must be accountable: they must be able to show that everything is proceeding as agreed with the Metasystem. This is an essential aspect of the resource bargain; it's the way the Operational element demonstrates that it can justify the continuing allocation of resources from System Three. The human Viable System has without doubt the most thorough network for demonstrating that all is going well. Every part of the body sends continuous messages to the base brain which knows just what's going on in real time. During periods of intense activity, this information is used by the base brain to modify the flow of adrenaline to the organs and muscles to optimise their operation. Beer's design for an equivalent system in an enterprise is based upon near real-time monitoring of all System One activity and a set of statistical filters assessing the information. The System Three office would have a big green light or a continuous tone which would mean "everything is OK". As soon as any of the measurements moved outside acceptable limits, the light would go off, and other signals would identify the source of the problem. But whatever the design, the Operational units must have a way of justifying their allocation of resources. The Command Channel (1): Intervention Rules.Inevitably there will be problems. What happens if one Operational unit begins to deteriorate due to machinery breakdowns, all the trained personnel leaving suddenly, or something completely unexpected like a flood? In some cases the unit can cope, in others it may not and this may threaten the survival of the entire enterprise. Clearly, there must be rules in place to deal with this. In certain situations System Three has to be given the mandate to intervene within an Operational element. For example, if the information shows that productivity is down, wastage is up and morale has collapsed, then it's essential for System Three to intervene. Intervention means loss of autonomy and is only permitted when the cohesion of the whole system is at risk. Intervention rules must be defined clearly, so that each Operational element knows it will be left alone unless it transgresses the agreed norms. All of this needs careful design. Beer has a simple recipe for deciding on the level of autonomy which can be allocated to an Operational element . He says autonomy should only be forfeit when system cohesion is at risk. So, if the actions of one Operational unit threaten to shake apart the whole system, its autonomy must be forfeit. In all other cases it should be left to function within the resource bargain - it is, after all, designed to be autonomous.The Command Channel (2): Legal & Corporate Requirements.By now it should be clear that the approach used here is in no way hierarchical and uses authority only as a last resort. The practice of senior management to interfere in all aspects of the business has been dismissed not for political reasons but purely from the Laws of Variety - it just can't be done competently. However, here we have a case in which the Operational Units, conceived as working with maximised autonomy, must obey a higher authority. System Three will ensure they pay taxes and stick to legal guidelines on (for example) Heath and Safety and employment. System Three will also ensure that the Operational elements stick to company Policy, regardless of the financial advantages. This may concern equal opportunities, or remuneration or a commitment to give money to charity. Some years ago a Suma member suggested that we set up a separate department staffed mainly by part time labour from the job centre. Figures suggested we could make money this way (labour costs were significantly below usual levels) but the proposal was well outside our Policies on employment and pay. Corporate Suma said no. System 3* Audits and Surveys.The final link between System Three and the Operational Units is called System 3*, and goes directly to the Operational bits of System One. It's job is to provide whatever information is needed to complete the model which is needed by System Three. It's inevitable that System Three will encounter situations in which it just doesn't have enough information to know what's going on. Regardless of the kind of information it may need, this is the job of System 3*. It may involve a study on buildings or machines or on the incidence of back injuries or on any aspect of the goings-on within the Operation. System 3* is often referred to as looking for signs of stress. In the original physiological model System 3* was based upon a nerve called the vagus which reports back to the base brain on signs of stress in muscles and organs. In the VSM this function has been extended to give System 3* the job of topping up the information needed by System Three. SUMMARYSystem Three deals with the whole of System One (all the Operational units) and looks at the way they interact. System Three is concerned with improving the overall performance of System One, so its main job is optimisation. In simple terms, System 2 deals with problems between the Operational units (its function is stability) whereas System Three makes positive suggestions as to ways of improving overall performance. In order to do this, System Three allocates resources of people and money. It may see that by cutting back in one area and by re-allocating those resources in another, the overall performance may improve. System Three needs to know how each Operational unit is doing, so it can continuously re-think its own plans in the light of changing circumstances. It therefore needs the Operational units to be accountable. Ideally, System Three will have a complete and up to date model of everything it needs to know about System One. From time to time System Three will need further information about the Operation and will ask to do audits and surveys. And finally, System Three must have the ability to intervene within an Operational unit if it believes that unit is threatening the viability of the whole system. DRAWING THE VSM - adding System Three

Note: Remember this is the Preliminary Diagnosis which is concerned only with the identification of the five Systems. So the job at this point is only to specify which parts of your enterprise do System Three stuff. The lines which you have drawn are to sketch in the connections between System Three and the Operational units. Later all of these interconnections will be dealt with in more detail, but it's far easier to build up a framework for the entire system-in-focus, before delving into the way the five systems interact. System Three: ExamplesSmall Group System ThreeAll of the Optimisation functions are carried out by the team-mind which constantly assesses what's going on, and acts accordingly. Accountability is total as the people doing the work and the managers are one and the same. A complete analysis of all System three function revealed no inadequacies whatsoever. Suma 1991The Finance Offer and Finance Committee allocate budgets on a yearly basis. This is thrashed out in discussion with the various departments, and decided on the basis of optimisation - how to allocate the money so as to get the most from Suma as a whole. The personnel budgets are decided in a similar way. Departments are asked how many people they can manage with, and this is optimised. Accountability is very patchy. There is no standard departmental system to account for how the budgets are spent. Major mistakes are obvious anyway, but regular quantified reporting has yet to be established. Audits are common and emerge from areas of interest. How much are we spending on back treatment? What skills do we have that are unused? Do we need to rotate jobs more regularly? Reports will be produced and the subject discussed. Intervention rules have still to be defined. In theory a department could become inefficient (especially in slack times) and no-one would know. Thus an acceptable lower performance level and intervention rules are not possible. Mondragon Co-ops 1991The body which articulates System Three for a group of autonomous member co-operatives describes itself as stimulating the co-ordinated joint development of the co-operatives incorporated in the group Synergy is perhaps the single most used word when talking to people about this function. There are many examples of how this is carried out.

These functions are carried out by meetings of managers from the various member co-ops. Step 6: SYSTEM 4PURPOSE: To identify those parts of the System-in-Focus which are concerned with Future plans and strategies in the context of environmental information.An example: a company may have one year of its lease left. A number of possibilities are available: it could re-negotiate, the lease move to another rented site, buy an existing building or build a new one. Each of these options needs to be researched in some depth, and the most likely alternative selected. Throughout this process, System 4 must be referring constantly to System 3, to ensure that the Operational constraints are considered. How many square feet? How much head room? Access to motorways? How much office space? Any specialised manufacturing facilities? Clearly, when System 4 has recommended a number of options, it will require site visits from System 3, and the interchange of ideas will continue. PRELIMINARY QUESTIONWHICH PART OF YOUR SYSTEM-IN-FOCUS PRODUCES STRATEGIES FOR FUTURE PLANNING? (Remember, this is about the System-in-Focus, not about the embedded S1 Viable Systems ... You may find that there is no focus for System 4 in your organisation. In the co-operatives I've worked in, this kind of activity is usually undertaken as a last resort. The Viable Systems Model asserts that for this function to work properly it must have a continuous focus: somewhere in the System-in-Focus someone must be looking at the environment and thinking about ways of dealing with a largely unknown future. In the following section, you will find an exercise concerning System 4, and a worked example. When you have completed it, you should have a good idea about the System 4 activities which you organisation ought to be undertaking. When its finished, you should think about the question posed on this page: (What is System 4 in your structure?) and decide whether you think it can do the job of continuously adapting to the future. System 4 Exercise

Worked Example: HWMC 1985

There were several more entries but they seemed to fall into four categories. After a few attempts the diagram looked like this.  This illustrated the main activities and how they overlapped, and thus gave a good representation of the issues with which System 4 had to deal. DRAWING THE VSM - From Step 6 - adding System 4

Step 6: IDENTIFICATION OF SYSTEM 4 - examplesYou have now drawn in System 4 on your VSM diagram. Examples of System 4 are as follows: System 4 - Suma 1991Future planning is given occasional consideration by groups and individuals. The Futures committee looked at possibilities for diversystem-in-focusication but didn't produce any proposals. A recent five year plan decided only to continue to proceed in same mode. In summary, there is no continuous focus for System 4 activity, and thus very little future planning. System 4 - MondragonMondragon has a firm commitment to Research and Development; its System 4 keeps in touch with developments in all aspects of robotics, production techniques, new products, and computerisation. Mondragon has built its own R & D facility. It is in touch with those aspects of its external environment which may exhibit novelty (e.g. European Space Project). It is currently looking seriously towards the unified European market in 1993 and planning accordingly. Step 7: SYSTEM 5PURPOSE: To identify those parts of the System-in-Focus which are concerned with Policy. Policy concerns the ground rules which affect everyone in an organisation. In the Viable System, policy is the domain of System 5. It may best be described as "Top Level Ethos", and its role is to become involved in the complex interactions between Systems 3 and 4. System 5 has two main functions: Firstly, to supply "logical closure": The loop between systems 3 and 4 is potentially unstable and must be overseen Metasystemically. Secondly, to monitor the goings on in the whole organisation. These must be constrained by policy. There is, of course, nothing to stop System 5 wielding its own authority (for example ... demanding that System 4 begins to study a particular issue and that System 3 responds to this ... and that the eventual outcome is passed to the Operational units to be elaborated into a production plan) but this is a rare occurrence. System 5 provides the context, the ground rules, the ethos. Who is System 5??? If your mind works like most of us the answer to this question will be something like Henry Ford or Walt Disney or some other hero who dominates the policy of the enterprise. (Any colour as long as it's black ...). Beer has written at length about the way that all elements of the Viable System are mutually dependant, and that giving one any more importance than another is clearly wrong. (How viable would Aristotle have been if any of his major organs had closed down??) The question of who System 5 actually is has to be answered very simply as everyone involved in the system. At the governmental level it should be described as "the Will of the People", within the co-operative it's the same and systems must be designed to ensure that's how it works. (Again notice that Mondragon seem to have grasped the essence .. they describe their General Assembly as "The Will of the Members"). At Suma, the Hub/Sector system evolved to provide a means of ensuring that policy can involve all members on a continuous basis. To my knowledge this is the only System 5 which works in this way with large numbers: usually systems will involve a few meeting a year. DRAWING THE VSM - from Step 7 - adding System 5

Step 7: SYSTEM 5 - examplesYou have now drawn in System 5 on your VSM diagram Examples of System 5 are as follows:

REVIEW: THE VSM IN ITS ENTIRETY

Step 8: PRELIMINARY DIAGNOSISBy now you have:

You have also put all of this together on a large VSM diagram, which will give a picture of your System-in-Focus in its totality. Now cross out those parts of your organisation which appear on the VSM from your original list. Remember to be clear about the System-in-Focus. Anything about the internal workings of the Operational elements should not appear on this diagram. (So .. in Suma's case .. the optimisation techniques used within each department don't appear. They are the concern of the next (smaller) level of organisation. The boxes 2, 3, 4 and 5 refer to the whole of Suma.) If you can't put anything in some of the boxes, you are in the same position that I was. There was effectively no System 4, except when it was unavoidable, at Suma. At this point you should take some time to consider the implications of the preliminary diagnosis. Some of the five functions will be performed by people or departments which clearly don't have the resources to do the job adequately. In some cases the entire Metasystem will be performed informally, and that may be fine (See Case Study on HWMC). There will be some jobs which are left on your list after filling in the VSM. Are they necessary? Some will be support jobs, like machine maintenance. The computer department is a facilitator, which makes things happen more smoothly and quickly. Both these jobs are clearly useful. But what about some of the committees? Are they really essential to viability? At the end of this process you should have

This concludes the Preliminary Diagnosis. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||