Introduction Preface Section 0: Cybernetic Eyes Section 1: The Quick Guide to the VSM Section 2: Case Studies Hebden Water Milling 1985 Triangle Wholefoods 1986 One Mondragon Co-operative 1991 Section 3: Preliminary Diagnosis Janus interlude Section 4: Designing Autonomy Section 5: The Internal Balance Section 6: Information Systems Section 7: Balance with the Environment Section 8: Policy Systems Section 9: The Whole System Section 10: Application to Federations Bibliography Links Appendix 1: Levels of Recursion Appendix 2: Variety  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |

Section 6: INFORMATION SYSTEMS

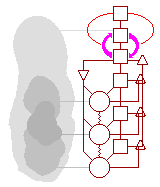

Information Systems: The VSM approachIf you look at the Inside and Now of your VSM diagram there are several areas in which information is crucial to good design:

All of these factors require thorough information systems. Traditionally information systems within a business are primarily concerned with financial information. They generally involve historical figures, so that after the monthly figures are produced someone may say "We have just realised that the business lost money last month because of something that happened in Factory 27" Which is, of course, too late. The other aspect of traditional information systems which is superseded in VSM theory is the production of huge print outs from a data base, most of which are never used. Central to the VSM approach is the production of only what is important. If information says "All seems to be going as usual" then nothing needs be done. Consequently, there is no point in printing the report. The information systems used in the VSM are fundamentally different from traditional systems in that:

Closing the LoopThe overall principle is clear - closed loops work and open loops don't. In traditional businesses the loop is closed in a number of ways: Work hard - get paid - keep the job - satisfy the boss - work harder and so on. The loops are closed with reward systems involving money (and sometimes job satisfaction) and with punishment systems involving the fear of reprimand and eventually losing the job. All of this works as long as the monitoring systems are adequate enough to keep an eye on the work force most of this time. The problem is the schism that emerges between the motivation of the manager (as much work for as little money as possible thus maximising profits) and the work-force (the opposite). Example 1: SumaThe following example is taken from some of the experimental work at Suma:

So you examine the time series and say nothing if its going up and down as you'd expect it to. But, if there's a sudden leap or plummet, something important has happened, and it's crucial that the alerting signal which is called an algedonic is generated. Beer describes algedonics as signals which scream "Ouch it hurts!" CyberfilterCyberfilter is a computer program which takes care of all of this stuff on indicators and algedonics. You work out your performance indicators at the end of each day and put them into the program. The history of each indicator can be displayed as a graph. It then analyses the graph and tells you if something significant has happened, that is, it generates algedonics. The program also does several other things involved with short term forecasting and planning, but its main functions from my point of view are:

Consider the following crises: a) The scales breakSuppose that the scales (which are used to weigh all the pre-packs) get damaged slightly and thus all the packs are 10% overweight. No-one notices during the day, although there is slight discomfort about the lower yields. At the end of production, the indicators are worked out and it's clear that wastage has leaped from 2 to 10 %. In this crisis, everything is checked, the problem is identified and an engineer is called. (This actually happened a few years ago, but wastage was only monitored infrequently, and no-one really knows how long we were giving away vast amounts of food ... ) b) Change in PersonnelAfter some years of efficient production the members of the department feel like a change, and new personnel are chosen. Some training takes place, but after the new personnel are established all the indicators start to slip. Initially the information goes back only to the pre-packing department, but after a further two weeks no improvement has been made, and the algedonic is sent to the co-operative as a whole and an enquiry is made. The previous workers are called back in, the situation is sorted out with more training and perhaps some re-allocation of people, and the original performance levels are regenerated. (Again this happens all the time in co-operatives but as there are no performance indicators, the new team has very little basis on which to learn. In some extreme cases, the decline in standards resulted in a department being shut down, but only after the quarterly accounts showed that money had been lost.)

SummaryThe essence of all this is the design of an information system which:

Example 2: MondragonOne of my original problems with the idea of performance indicators was how to deal with performance which is not easy to measure - you can record the number of boxes produced, but how do you measure something like tidiness or morale? One solution to these problems came from the Fagor refrigerator factory in Mondragon. They had changed their production line into a series of autonomous work groups in order to address problems of motivation, and had identified performance indicators as the appropriate means of handling information. As expected, they measured productivity and other quantifiable aspects of their working situation, and this gave them a new degree of autonomy. For example, during my visit to Mondragon there were a series of festivals which lasted all night and (as expected) the production figures fell dramatically on the following day. This is not seen as a problem as long as the figures rise on subsequent days and the weekly average reaches the usual standard. All of this is under the control of the people on the shop floor - the algedonic is only generated if the weekly average is affected. Thus a comprehensive monitoring system can enhance departmental autonomy. But they were also able to deal with less tangible elements. They do this by negotiation: Once a week a representative of the work group meets with the foreman and they go through a number of performance indicators. As an example they discuss autonomy which is registered on a scale of 0 to 10. The group is aiming at complete autonomy and may feel it had almost got there: "We think 9 for autonomy". The foreman may disagree "But on Wednesday you couldn't deal with a problem and had to ask me to sort it out for you. I think 6." Eventually they may agree on 8. All these numbers are written up and displayed on notice boards. They don't plot graphs, but the flow of numbers provides a reasonable picture of the way things are going, and provides the feed back which is one of the more important aspects of this system. This concept of negotiated performance indicators opens up many possibilities. In a co-operative it seems more likely that the negotiator would be someone who used to work in a particular department, understands how it functions, and has an interest in maintaining its standards. How to Design the System1. Performance IndicatorsNegotiations are needed between the department in question and whoever is responsible for the allocation of resources. (Remember this is also designing the accountability systems which complete the resource-bargain loop between Systems 1 and 3). The question is "What numbers do I regularly quote when I'm talking about how well the day has gone?" For example "Only three tonnes of muesli all afternoon." or "What a good day! I completed four pages of the ledger." These indicators need to satisfy both the department and the resource allocator that they give a complete picture. It will then be the responsibility of the department to measure and plot them every day. 2. AlgedonicsSome variation will be inevitable. It may take some time to establish what an algedonic actually is. So ... 5% variation in productivity is fine as long as the variations even out. A continuous decline for 4 days is unacceptable and constitutes an algedonic. A 10% variation needs to be examined. And so on. If you decide to use Cyberfilter, this kind of decision will still have to be made. The responsiveness of the program has to be established, or it may churn out algedonics every time someone sneezes. 3. Time Periods.Each indicator must be studied individually. You must then decide how long it should take to deal with problems, and how long a problem can be permitted to continue until the viability of the whole co-operative is at risk. So ... you have 5 days to deal with wastage problems, 10 days to get out-of-stocks back to acceptable levels, and so on. These time periods must be agreed in advance, as when a crises hits the system, the framework for dealing with it must be already established. 4. Loss of AutonomyAssuming an indicator becomes unacceptable and continues at that level beyond the pre-agreed time, then the whole co-operative gets notified and that department loses its autonomy. The nature of this loss should again be designed. It may involve a complete analysis of the problem, or the appointment of an agreed trouble-shooter or whatever. But again this should be agreed in advance. Step 12 Examine your Information Systems

|

||||||||||||