Introduction Preface Section 0: Cybernetic Eyes Section 1: The Quick Guide to the VSM Section 2: Case Studies Hebden Water Milling 1985 Triangle Wholefoods 1986 One Mondragon Co-operative 1991 Section 3: Preliminary Diagnosis Janus interlude Section 4: Designing Autonomy Section 5: The Internal Balance Section 6: Information Systems Section 7: Balance with the Environment Section 8: Policy Systems Section 9: The Whole System Section 10: Application to Federations Bibliography Links Appendix 1: Levels of Recursion Appendix 2: Variety  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |

Section 4: DESIGNING AUTONOMY

Autonomy or AuthorityIf you have organisational problems such as lack of efficiency or jobs just not getting done there are basically two options:

The first option has been used for hundreds of years in all kinds of society and it is only recently that its limitations are becoming clear. The Management Gurus in the United States are now coming out with statements like "Train the hell out of your workers and then get out of their way". This new emphasis on making all workers more autonomous has been obvious to people in co-operatives for decades - what has been lacking is the systems needed to ensure it works properly. There is no point in saying "OK ... you're all autonomous now" and expecting the rest to take care of itself. The first essential is for each Operational unit to be clear about its role within the whole organisation and should therefore produce its own Mission Statement. This may take some negotiation with everyone else, but will ensure that the Operational unit works as an integrated part of a greater whole.

Allocation of ResourcesWhatever your organisation, the Operational units will need resources. They will need money and people in order to carry out their function. This is the point at which the design process can begin. System 3, which oversees the collection of Operational units must have a financial aspect which is concerned with the overall financial picture for the business. It is the job of financial System 3 to allocate resources. Usually this will occur in the yearly budget rounds. Each unit will say "We need £pound; £pound; £pound; in order to do our job", System 3 will add it all up and say "Sorry, we don't have enough to give everyone everything they want, who can make cuts?" This process will continue until either the necessary cuts are made .. or .. System 3 will make decisions about who gets what, in the light of what's best for the whole organisation. (That is ... it optimises the allocation of resources). In most cases, the allocation will only happen once a year and thereafter, each Operational unit will do its job according to the pressures put upon it by the market or other parts of its own organisation. This one way process (here's the money you need, and that's the end of my job ...) works reasonably well as long as everything proceeds as normal, but is totally incapable of dealing with problems. The usual situation is as follows:

Thus:

Dealing with Problems: Intervention RulesThe question must arise: "If each Operational element is given autonomy, how do you stop standards from sliding?" The question is valid. A protocol must be in place which can deal with the possibility of a group of people loosing heart and of letting their performance deteriorate. The first part of the solution is accountability: if performance is measured and the figures are monitored, then at least the deterioration can be noticed. The second part is to define clear performance standards which the people working within that unit can aim for. The final part is to agree the terms on which any severe problems can be dealt with. This may be something like:

The details of this statement will vary depending upon the situation, but the loss of autonomy must be an essential element. The nature of the intervention rules should:

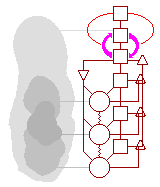

The essence of this system is to both encourage and underwrite Operational autonomy while ensuring that the worst case scenario is dealt with quickly and fairly. To do this, a continuous interaction between the Operational unit and System 3 is essential. The unit should be free to pursue its own development and respond to the demands of its environment, but within the constraints of being part of a larger whole. Step 9: Designing Operational Autonomy

Example 1: Mondragon.Mondragon exhibits most of the necessary elements of this system of autonomy.

Example 2: Council WorkersWhile I was writing this pack, the council arrived to re-lay the drive around my house. Two men arrived and put wooden boards into the ground to determine the level and orientation of the drive. Some time later, another crew arrived to lay the tarmac. They brought the tarmac around using a big tractor which didn't fit between the boards and smashed several of them into splinters. I asked what they intended to do and they said "We were told to use this tractor and lay the tarmac so that's what we have to do" So they laid the tarmac without guides. Diagnosis:

Clearly the situation is unworkable, unless the original plan is so thorough that it takes care of every eventuality, or unless the Man In Charge is there for the entire duration of the job. Inevitably, the plan cannot cope with the complexities of the situation and the Supervisor has several jobs which he is supposed to supervise going on simultaneously. The solution is (of course) to give the men doing the job the autonomy to control it themselves, but that is completely alien to the culture. I discussed this with one of the workmen who agreed. "But we're all supposed to be totally stupid and only able to do what we're told." |

|||||||||||||||||||