Introduction Preface Section 0: Cybernetic Eyes Section 1: The Quick Guide to the VSM Section 2: Case Studies Hebden Water Milling 1985 Triangle Wholefoods 1986 One Mondragon Co-operative 1991 Section 3: Preliminary Diagnosis Janus interlude Section 4: Designing Autonomy Section 5: The Internal Balance Section 6: Information Systems Section 7: Balance with the Environment Section 8: Policy Systems Section 9: The Whole System Section 10: Application to Federations Bibliography Links Appendix 1: Levels of Recursion Appendix 2: Variety  This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |

Section 5: BALANCING THE INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

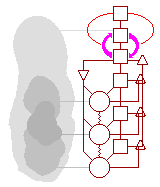

Internal Environment: Systems 1, 2 and 3The Inside and Now is the internal environment of the organisation. It includes the Operational elements, and Systems 2 and 3 which have the job of optimisation, stabilisation, gathering the information needed for these functions, and passing information to and from the rest of the organisation. In the next few pages we will be looking at the design of all of this. But first: review all the elements of the Inside and Now by considering your VSM diagram of Systems 1, 2 and 3. It will look something like this.

Operational and Environmental InteractionsIf you take your VSM picture and look at the Operational units and their environments, you will have something like this.

In a study on a federations of co-operatives, these two perspectives proved to be of crucial importance. Environmental OverlapsThe environments consisted mainly of markets and suppliers and the crucial overlap was the delivery areas. Many of the problems in establishing the federation could be dealt with by re-defining the delivery areas to concentrate on local service. Suppliers (the other main part of the environments) also required consideration. By making each warehouse specialise in a limited range of suppliers, the expertise of the group could be improved. Operational ConnectionsThe movement of goods between warehouses proved to generate interesting ideas. One warehouse with a surplus could use the others to reduce it. Short best-before-dates could be moved more quickly. Shortages in any part of the federation could be dealt with quickly by supplies from another. Having made the Operational units as autonomous as possible the next step is to look at these two channels and to see if any issues can be dealt with in this way. The steps involved in this procedure are given below. Step 10 Operational and Environmental Interactions

Designing Systems 2 and 3In the previous pages we have looked at

All of these techniques enable the Operational units to deal with day by day problems without interference. They are ways of generating the maximum amount of autonomy within the limits of the larger whole. The question now is: You have already identified the parts of your organisation which do these jobs at the moment.

But are your existing systems adequate? As the rate of change of markets continues to escalate it becomes more and more essential to monitor and deal with problems on a continuous basis - and so monthly committees are becoming progressively more useless. How thorough is the information you have from your Operational units? How good is the model of System 1? How up-to-date? If this is inadequate, then any decisions made by Systems 2 and 3 will be made in some degree of ignorance. After thinking about issues like this you may decide to increase the capabilities of Systems 2 and 3 in order to ensure they can do their job. This may involve more time, more people, more thorough monitoring or whatever. Whatever you decide, it is essential not to interfere with the autonomy of the Operational units, unless it is absolutely necessary. The steps involved in completing the internal balance are given on the next page. Step 11: Completing the Internal Balance (Summary and Conclusion)

Designing the Internal Balance: ExamplesExample 1: SumaSuma's internal balance was restored as follows

The combination of local autonomy, improved information systems, and the new System 2 and 3 jobs restored the balance. Example 2: National Manufacturing CompanyA major national company was the subject of a VSM diagnosis which revealed severe shortcomings in the way that information on stock levels was sent from the local warehouses to the central manufacturing facility. This led to incorrect assumptions as to the products which needed to be produced and huge inefficiencies at the factories. On several occasions late information would result in a change of plan, involving resetting a production facility which had taken eight hours to set up. A study of the internal environment revealed that establishing accurate information systems was all that was needed to restore the internal balance. Example 3: (Hypothetical) Federation of three WarehousesThe traditional approach to ensure that the three warehouses work together efficiently would be hierarchical: appoint 3 managers and put them all under the control of a general manager. In VSM terms, this is the use of the command channel (C4) but this inevitably interferes with the autonomy of the warehouses and thus their ability to deal with their own environments. Consider the other alternatives:

Once these systems have been established, the need for any sort of authoritarian system should become completely unnecessary, and Systems 2 and 3 may be designed with relative ease. Example 4: Chile 1972Beer's work in Chile was essentially to integrate the entire social economy into a single system using the VSM. He established communications links between most of the nations factories and a central gathering point in Santiago which implemented Systems 2 and 3. Each factory measured its performance daily and sent a set of indicators through communications systems based on microwaves and telexes and in some cases messages on horse back. A suite of computer programs analysed the indicators, and sent any alerting messages straight back to the relevant factory. (This was 1972 and computers were still very expensive. Most of this would be done by Micros today, thus enhancing local autonomy). The integration of most of the nation's industry into a single system had some dramatic consequences. During 1972 the CIA initiated a strike of 70% of Chile's transportation. They had embarked upon a policy of "destabilisation" and had bribed the owners of the trucks to refuse to work. Immediately, the alerting signals began to flood into Santiago. No raw materials here, no food there. This began a period of intense activity as the signals were processed and plans were produced to provide as much of the nations transportation needs with the 30% which was under the control of the Government. Because the information systems were so thorough, the people in Santiago knew exactly what was needed, by whom, what trucks were available and so on. During the next 36 hours all the emergencies were dealt with, everything which was needed was delivered and some factories said that they had never had better service. For this situation, Systems 2 and 3 were clearly able to deal with the demands of the Operational units, despite the fact that 70% of the distribution system was unavailable to them. Most of the success is due to the conception of an integrated economy, and to the information systems which enabled the people dealing with the crisis to know just what was involved: their models were thorough and current. The US Congress reports of that era show a great deal of surprise at the stability of Chile under Allende, and that in order to attain their goal of bringing Pinochet to power they had to make far greater efforts than they had expected. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||